Questions about learning root notes and why comes up a lot by guitarists.

In this article, I will attempt to answer some questions you might have about root notes, and hopefully encourage some people enough to spend time to learn them.

Learning root notes might sound like a lot of work, but I recommend that you learn them as you go, for example, learn the root notes of an A major barre chord shortly after learning the shape.

Don’t try to learn all the root notes for everything in one go, as that would probably get a bit boring! Instead, you could read through this to pick up the main points, and perhaps check back here when you learn a new barre chord or scale to refresh your memory if you need it.

What are root notes?

Root Notes in Scales

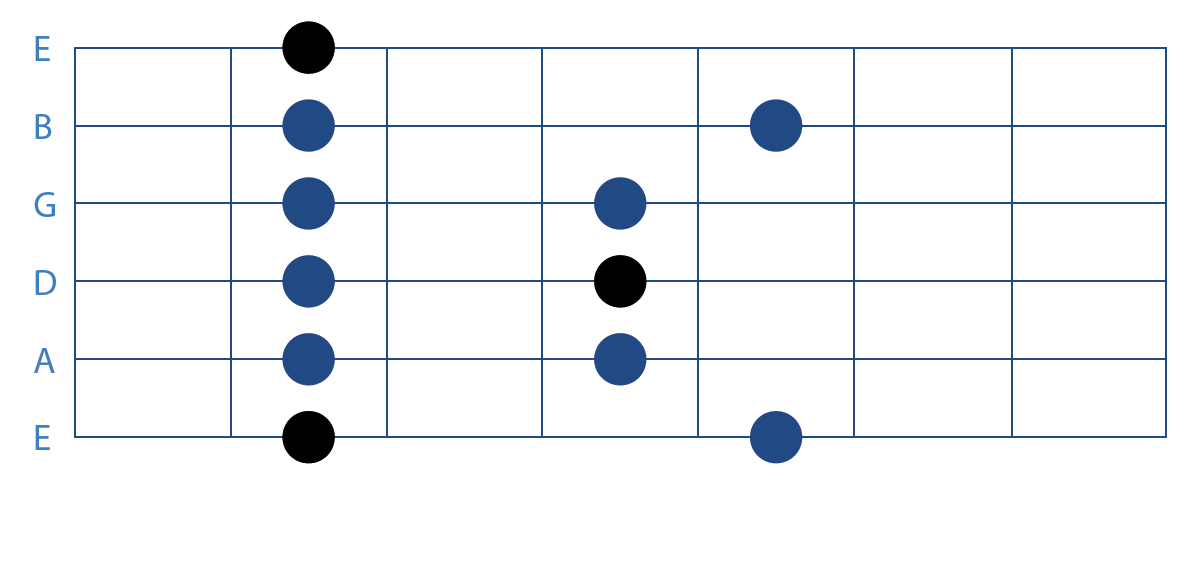

In scales, the root note is the first note in the scale. This is also the root note of the key of the song. In a 2 octave scale, there will be 3 root notes: The first note in the first octave, the first note of the second octave, and you normally end on the 1st note of the 3rd octave.

These are important to know because when you are soloing, it’s often a good idea to resolve to the root note at the end of the solo.

Another good thing for knowing the root notes, is that you could start soloing half way through a 2 octave scale, by starting on the second root note. In RGT grade 5 and above, you actually are required to know many scales in this way, by playing 1 octave scales in 5 positions. They are all actually the same notes,but played starting on various root notes. So here you will be forced to learn the root notes! The idea of this is useful: to be able to play the same riff all over the guitar neck but a acheive different tones, or be able to apply different techniques such as hammer ons or slides in different places that you couldn’t in others.

Root Notes in Chords

Major chords are made up of 3 notes (a root note, and two others). Almost always, the first note in any chord is the root note. The root note of an A chord is A. The root note of an E chord is E. Easy.

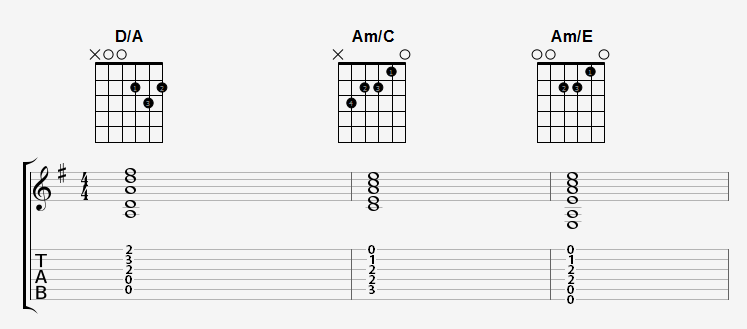

In standard major and minor barre chords on the E string, there are 3 root notes in total. This is the first note, last note, and the one that you hold down with the little finger. Knowing where root notes are in other chords, and how they are constructed is usefull for picking out those notes if you want to, or for creating variations of the chord. If you want to find out more, do a quick search on here, or on google, for ‘chord construction’.

Root Notes in Arpeggios

Knowing the root notes in arpeggios is similar to learning about chord construction, because an arpeggio is basically the notes that make up a chord in chronological order, played for 1 or more octaves. For example:

- a C major barre chord is made up of the notes C E G.

- the order that these notes are played in on fret 8 of the E string is actually C G C E G C when you use the major barre chord shape on the E string.

- The 2 octave major arpeggio shape on the E string would be played on fret 8 as well so it’s in C. The notes would be in order though, so they would be C E G C E G C. Knowing where the root notes are (the C’s) is helpful for starting the arpeggio half way through, or making your own custom arpeggios.